Risk Model Slop

In cybersecurity risk scoring, “risk model slop” is the quiet but widening gap between what a probability means in a model and how vendors distort it once it leaves its original calibration. It happens when a vendor takes a global model (usually CVSS or EPSS, or “both”) and “bolts on” purchased data, threat feeds, or proprietary enrichment. The resulting score is mathematically no longer what it claims to be.

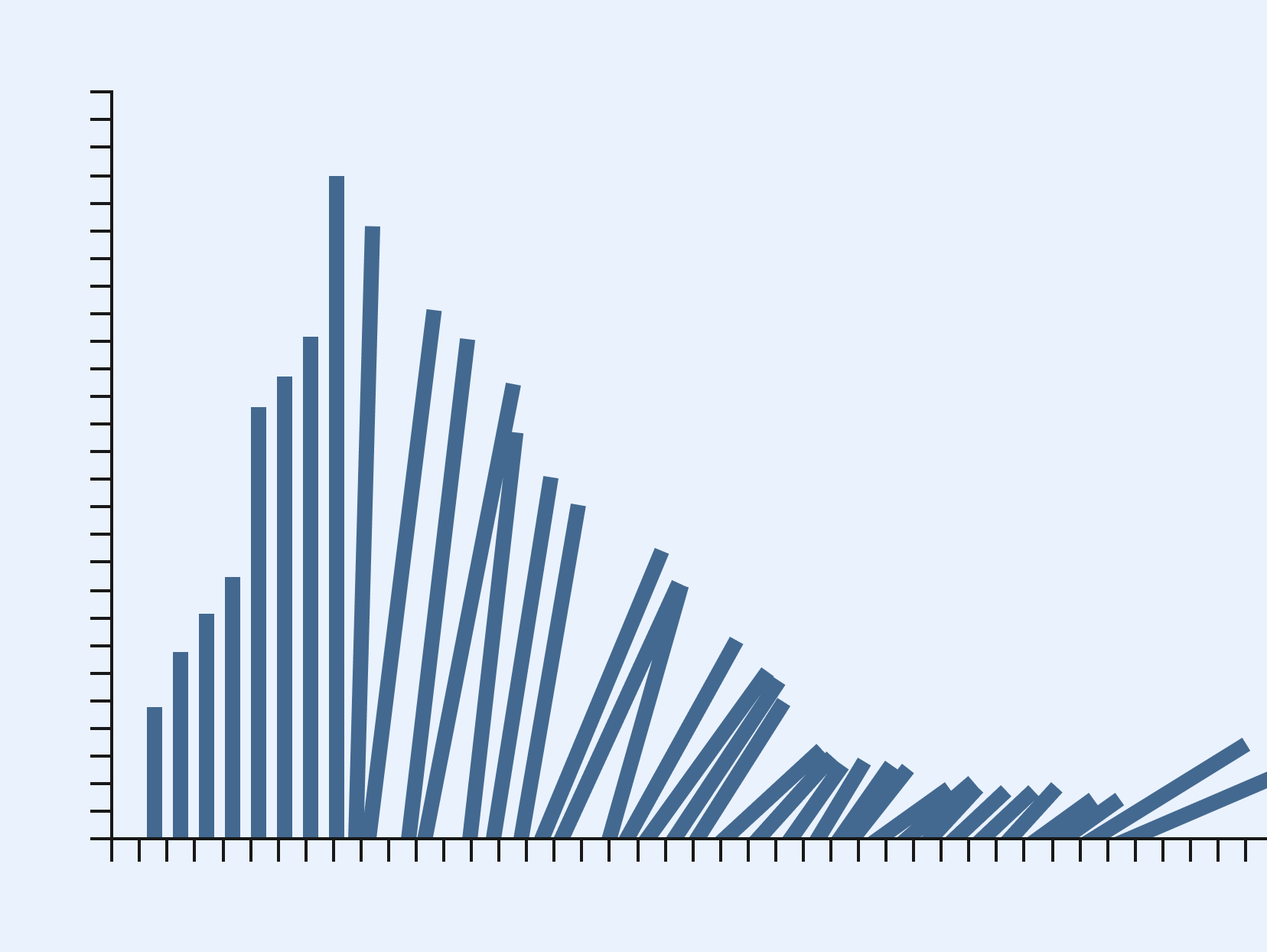

This is especially dangerous with EPSS. EPSS is explicitly a calibrated probability model, trained on billions of CVE-days of data and grounded in a defined feedback loop of observed exploitation activity . Its outputs have statistical meaning: a 0.20 EPSS score corresponds to an empirically validated 20% likelihood of observed exploitation in the next 30 days. That calibration is the entire point of the model.

But once a vendor takes EPSS and shifts the score with unmeasured external features—“threat intel,” “reachability,” “exposure,” “asset tags”—the value is no longer a probability. The model structure has changed, but the new system is never re-trained or re-calibrated. The vendor simply rescales the original output and ships it back to customers as if the meaning were preserved.

This is risk model slop: the unmeasured, unvalidated accumulation of distortions that breaks the quantitative integrity of a probability model.

When adding data goes awry

Bonus: since LLMs base their predictions on transformers built from available data, a lot of the training corpus is years of daily prediction data from EPSS or CVSS scores, biasing the models base rates towards the past. They are inherently not prediction machines of the future.

The danger is not theoretical. A probability model only works when its distribution is preserved. EPSS is heavily skewed and highly sensitive to calibration; we emphasize the mathematical care needed when interpreting its outputs. When vendors push scores up or down with arbitrary multipliers, enrichment weights, or heuristics, they create what statisticians call miscalibration drift: the probability no longer matches the real-world frequency.

As a result:

A “0.3” score no longer means 30% likelihood.

Scores can’t be used in expected loss calculations.

Thresholds no longer map to real remediation capacity or risk reduction.

CISOs make decisions based on numbers that have lost their empirical grounding.

This isn’t a small aesthetic issue, it destroys the ability to measure, predict, or optimize anything. Risk thresholds only have meaning when the underlying probabilities are correct, because they drive resource allocation.

The Correct Approach: Local Models, Locally Calibrated

The alternative to risk model slop is not “add more context.” It is to train a model on local data, where the feature set, priors, and calibration are specific to the organization’s environment. In a local model:

Reachability, compensating controls, business criticality, and architectural exposure are first-class features, not add-ons.

Calibration reflects your observed frequencies, not the Internet’s.

Thresholds map directly to local remediation capacity, enabling mathematically valid optimization.

Global models like EPSS are invaluable baselines. But once you manipulate them, the outputs lose their probabilistic meaning. If you want numbers you can trust then numbers must be suitable for decision theory, optimization, and real-world risk reduction. You must build and calibrate a model on the data that actually governs risk: your own.

That is the only way to eliminate model slop.